“Gerard examines the emergence of the Japanese performance car in New Zealand during the ’70s and ’80s, and makes a case for a new breed of classic car”

Right from the start, I have to admit that I’m a serious Japanese car junkie! Not just any cars of course, and while the ones that really dial my number are performance machines from the ’60s through to the ’80s, I have a general affinity for even the more mundane offerings from the land of the rising sun from that era and beyond.

It would be best to keep that critical factor in mind whilst reading this article — especially as nothing seems to polarize followers of the classic-car culture and other car tribes more than an admission of allegiance to the products from Japan. There are various reasons for a negative point of view — some date theirs back to a refusal to have any dealings with anything made in Japan as a result of the grim treatment of Allied servicemen during World War II, while others held to the belief that Japanese products exhibit a supposed cheap and tawdry quality. The latter criticism may have been correctly applied to some manufactured products emerging from Japan post war, but largely disappeared with the passing of that generation.

As well, in some quarters there is still the perception that cars built in Japan are missing some vital ingredient. Comments in various magazines I have read seem to suggest the vehicles concerned have an undefinable but alleged clone-like lack of character or, to use a common complaint opined by many supposed experts, they are soul-less.

There are plenty of other mass-produced performance cars originating from the US, Europe, Australia and elsewhere that have an inferior build quality, track manners and performance, but are considered thoroughbreds. Prejudice to real quality seems to be the prevailing situation — and what character is and how to define it, which is not exactly elaborated on by Japanese car detractors.

Then there is that often-heard cheap shot — rice burners. I struggle to understand the criticism here! High tech, small capacity, bulletproof, high revving, fuel-injected turbocharged motors capable of unleashing a tidal wave of power, in lightweight good-handling cars — what’s not to like? Especially when they suck far less juice than a gas-guzzling V8-powered dinosaur, while running rings around them in most aspects of road manners and performance!

However, perhaps the accusation that amuses me the most — usually the final line of defence, generally from muscle-car owners who have probably been outgunned — is that the Japanese rocketships lack ‘quality’. They seem to be suggesting that, inherently, Japanese classic performance machines have no intrinsic value, and are destined to become quickly relegated to the trash can. Of course, treasured antiques such as a low-revving pushrod V8-powered muscle car, restored via a heart-palpitating budget blowout, are viewed as magnificent pieces of retro engineering.

Historic Japanese performance cars

Times are changing, and more recently there has been a surge of awareness among a rapidly growing contingent of classic car followers that early Japanese performance is and always was very trendy and cool. This is something that has also been reflected in the pages of this magazine, and it’s not just nostalgia, as there is growing recognition as to the advanced and well-engineered quality of these cars. Indeed, there was no comparison with competitors from other nationalities in the same price bracket when it came to the levels of standard equipment offered. As well, Japanese cars were wonderfully reliable and, while not all the early examples handled brilliantly, their brakes were usually superb, their engines bulletproof, and they out-performed many of their rivals.

Character and mana is built on these attributes! OK, I’m a devotee, but I feel it’s time some of the hoary old myths surrounding Japanese cars were vaporized.

During the ’90s I owned four performance Japanese coupés from the ’80s, and they were all a driving revelation in comparison to the equivalent but rather more inferior English cars it had been my misfortune to operate prior to that time. The last of those cars passed through my hands in 2004, but left a passion in me for Japanese high-performance vehicles from that period, and those from the earlier ’60s through ’70s era. This story, in case you haven’t already gathered, is a bit of a celebration of the brash cult of the first wave of hyper- power from Japan.

The sun also rises

To understand the history behind the emergence of the Japanese performance car, we need to backtrack to the early ’60s and a time when Japan was rebuilding following the destruction of World War II. The major pre-war car companies had started to get back on their feet, courtesy of government support for a ‘people’s’ 360cc car initiated during the ’50s — with the US almost unwittingly helping to kick-start the Japanese car industry in order to support the production of the vehicles needed for its early ’50s conflict against the communists in Korea. The US idea revolved around building vehicles closer to the war arena, but this act of assistance to Japan was ultimately a factor in the downturn of the complacent, largely resistant to innovation US auto industry.

With a later government supporting a 2.0-litre engine capacity incentive, combined with the opening of the first Japanese motorways in 1963 and the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, the local motor industry received a further shot in the arm.

In those early years, two now legendary performance coupés appeared — the result of a growing sophistication of Japanese automobile engineering.

The futuristic, rotary-engined Mazda Cosmo 110S Sport in 1964 and the Toyota 2000GT of 1967 were stunningly attractive two-door automobiles. Combined with Honda’s superbly technical 1.5-litre V12-powered Formula One racing car in 1964 and ’65, Japan’s force of innovation was about to be felt within the traditional automobile building dynasties.

The Japanese miracle

To some extent, the early era of the Japanese auto industry following World War II was built around copying the best examples from other manufacturers. However, once their own infrastructure had evolved sufficiently, particularly by the mid ’70s, the Japanese were moving ahead of the shoddy quality and poor workmanship that marked many British and US-built cars of that era. Indeed, they totally lifted the bar, forging their own style with well designed and engineered small cars that were economical, and produced surprising power with total reliability.

The Japanese auto worker played a big part in this sea change, as they shared the investment with management in constantly improving the product. Assembly-line employees were constantly encouraged to come up with new ideas to promote efficiency, while design and profit sharing became a further incentive for progress.

This renaissance in automobile manufacturing was all part of the ‘Japanese miracle’ — the amazing re-emergence of industry in such a short time after World War II. This renaissance encompassed a stunningly diverse range of high-tech products — everything from portable electronic audio items to cameras and home appliances.

The emphasis was on developing exports, and this was achieved in a blindingly quick time. From the automobile perspective, both the British and American auto industry failed to recognize the tides of change. When that initial tide turned into a veritable tsunami, their demise was relatively quick for the British, while Detroit suffered a much more agonizing and slow collapse. The Europeans, with a somewhat similar focus on quality and efficiency, were able to thrive, running comparatively lean organizations similar to those of the Japanese firms.

Shabby build quality, and mounting pressure to release flawed vehicles not fully sorted due to economic pressures, hastened the British auto industry’s slide into obscurity during the ’70s and ’80s. Meanwhile the unwillingness of the American auto barons to accept the reality, that their continuing manufacture of gas-guzzling dinosaurs was no longer appropriate in a world coming to the growing realization that conservation and sustainability mattered, would come back and bite them.

The first oil shocks of the early ’70s should have provided an initial wake-up call for Detroit, but went largely unheeded — although not with the car buying public. The misplaced belief summed up by the often-heard mantra “What is good for General Motors is good for the country” saw the US auto-makers clinging to the belief that the consumer would always return to the showroom for the biggest status symbol. To the contrary, consumers defected in droves to vastly better engineered and more reliable offerings from the East. Neither the US or UK primary car-building industries would ever fully recover the ascendancy they once held.

Win on Sunday, sell on Monday

While most Japanese automobiles built during the ’50s were, of necessity, very conservative and utilitarian, the country’s car-construction industry was struggling to re-establish itself. Small four-door sedans (styled like Standard 10s) suited the local market, but initial attempts to instigate exports to the US began as early as 1957 (Toyota Crown) and 1958 (Datsun/Nissan 110).

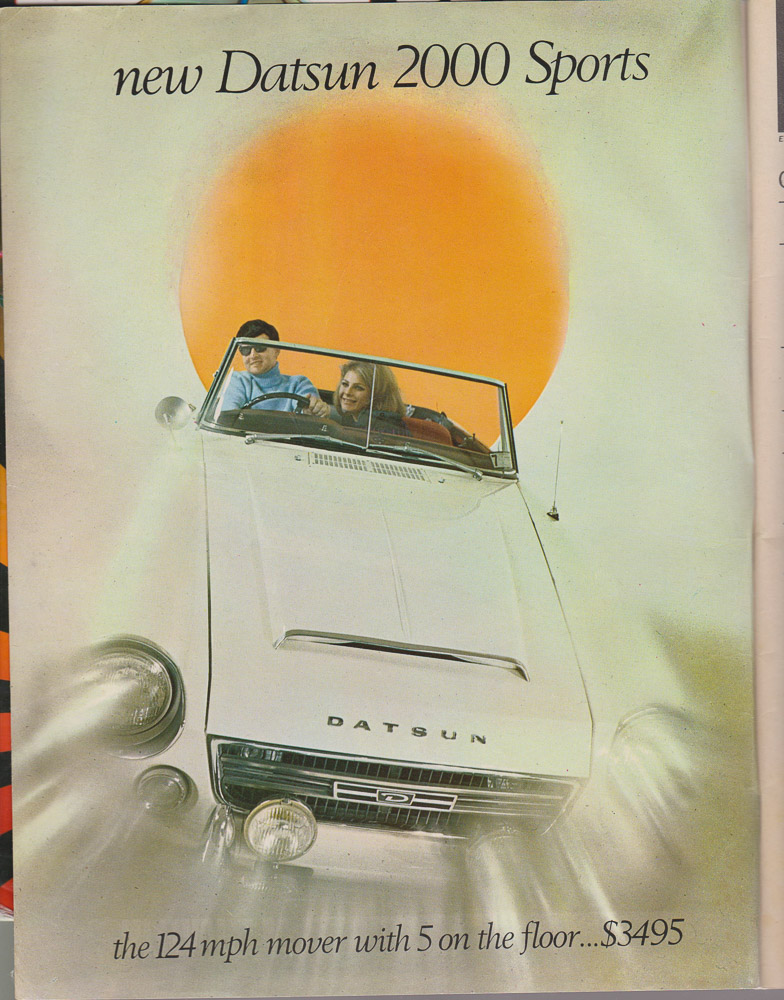

The mid to late ’60s saw a substantial growth in vehicle exports on a global stage, with Toyota and Nissan leading the way. Following the introduction of a more exotic tier of sporting machines such as the Toyota 2000GT, Mazda Cosmo 110 and Datsun 1600 sports car, new spice was added to the previously small commuter/family dominated image of Japanese manufacturers. There was, predictably, resistance in some quarters along with the institution of a tariff embargo, but slowly and surely, consumer awareness rose and acceptance increased.

Significant cars like the Toyota Corolla and Datsun 1600 began to build a reputation that cars powered by small capacity, strong, high-revving engines could be a lot of fun to drive. As well, the willingness of Oriental manufacturers to compete successfully on the race track also provided wonderful publicity.

Cars such as the John Morton–driven quasi-works Datsun 510 (a Datsun 1600 derivative) of Brock Racing Enterprises (no relation to the Australian icon) won the prestigious up to 2.5-litre class of the legendary Trans-Am series two years in a row from 1971–’72, defeating the previously unbeatable Alfa Romeo GTVs. This sort of dominance provided priceless advertising that money simply couldn’t buy.

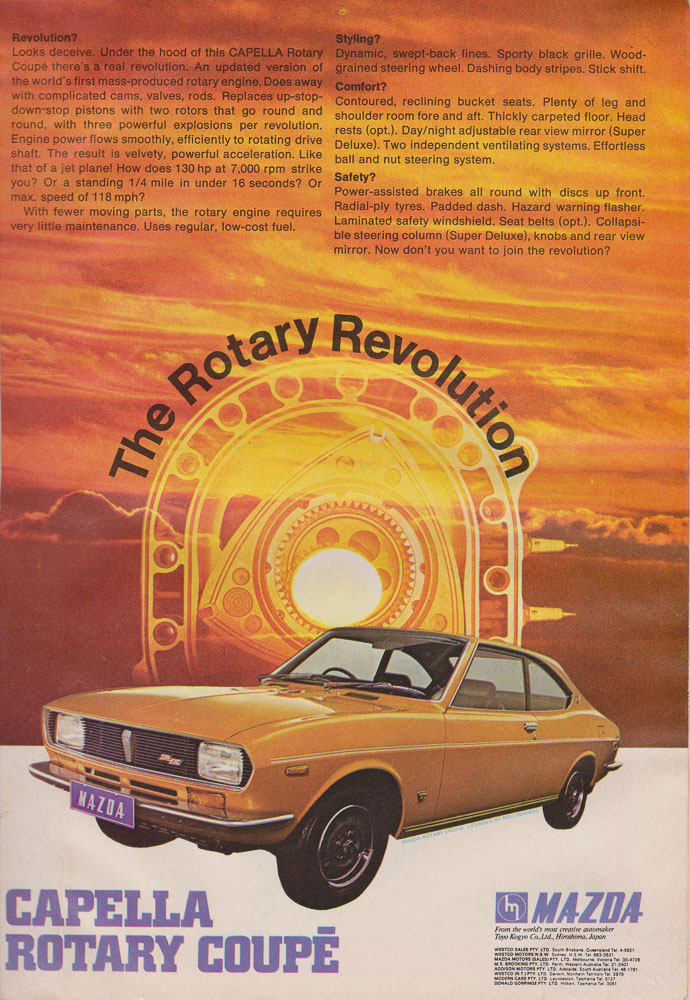

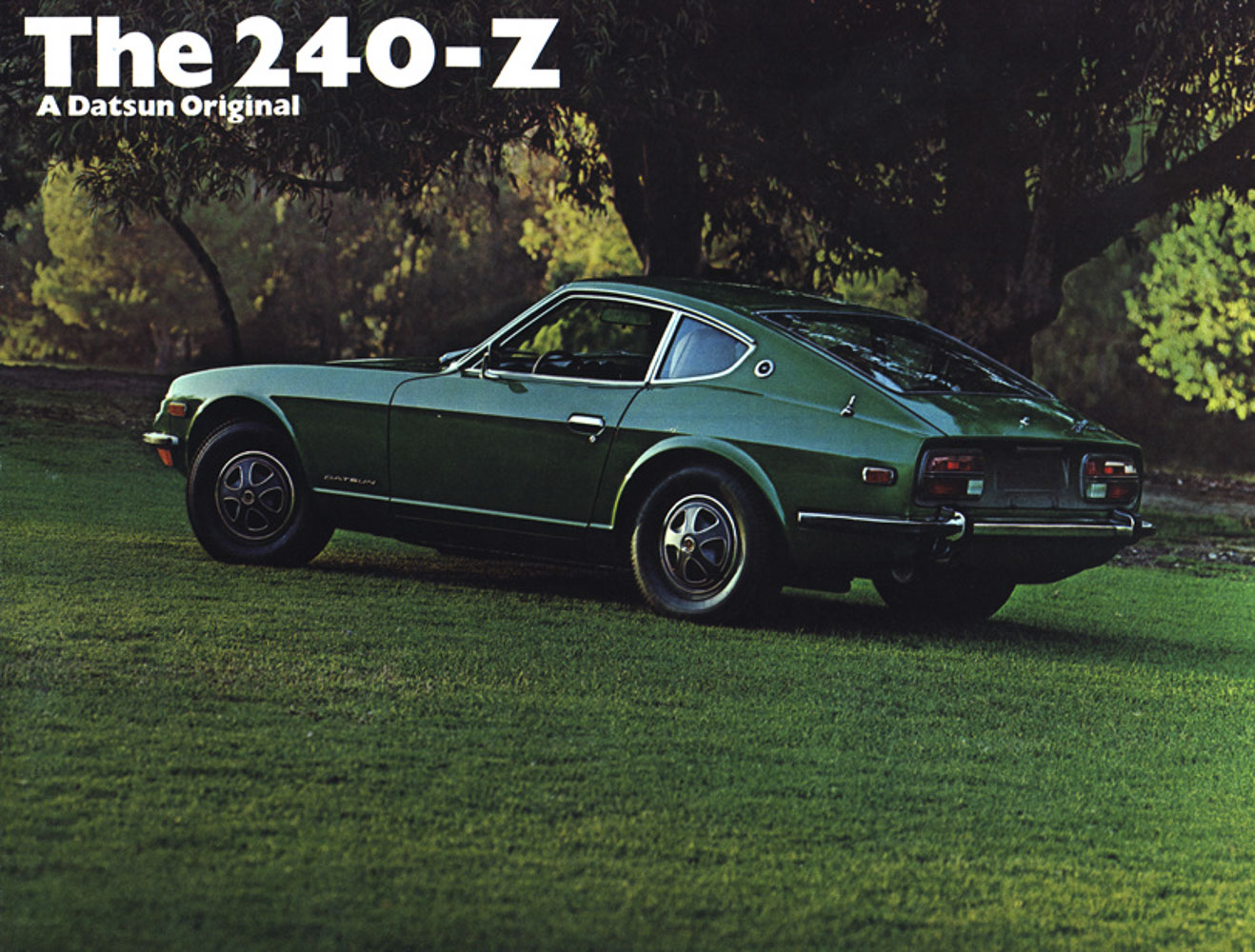

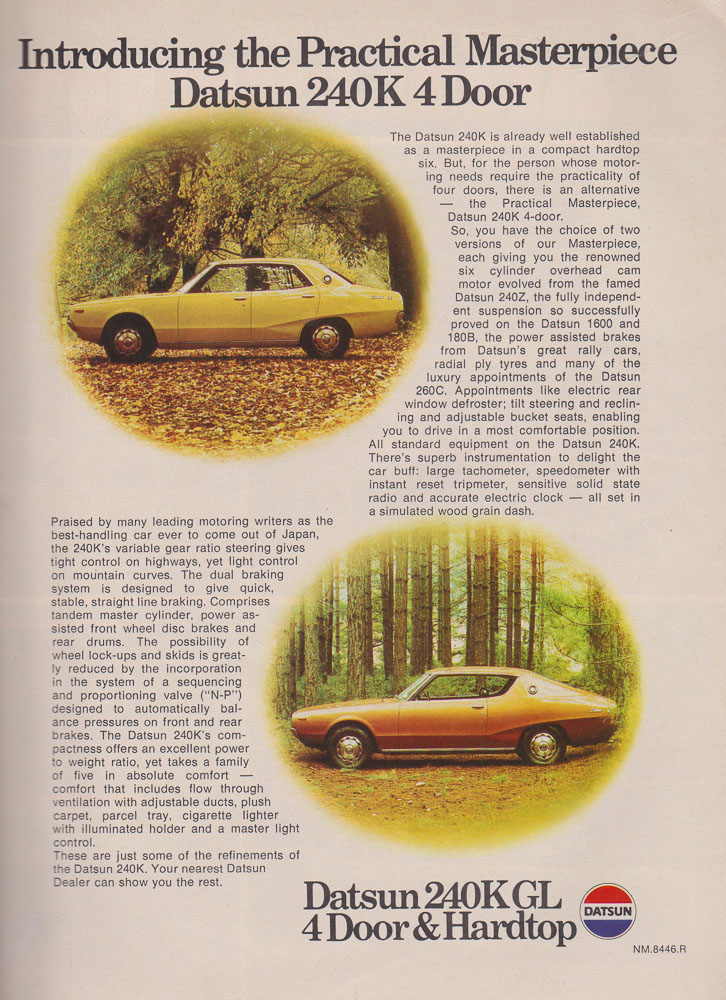

Other emerging cars which captured the imagination, and provided new levels of performance at reasonable prices, were the beautiful Datsun 240Z (1969), the rotary-powered Mazda Capella coupé (1970) and the evolution of the magnificent Toyota twin-cam motor as installed in the early Corolla TE27 Levin coupés in 1972.

One example from the mid ’60s, and probably the earliest exotic Japanese car to race regularly and with success in New Zealand, was the superb Prince Skyline GT campaigned by Carlos Neate during the 1966-’67 motor-racing season. Skylines with their high performance, twin-choke side-draught carburettors and straight-six engines, were serious contenders in the mid ’60s and survived the takeover of Prince by Nissan in 1968. Neate finished the 1966–’67 season in fourth place in the Group 2 Saloon Car Championship series, a pretty solid effort. As reported in NZ Classic Car (May 2003), Neate’s Skyline GT-B is very much alive, in largely original condition, and now resident in Australia.

Kiwi contenders

Other early Japanese cars racing in New Zealand included the early entry of a Honda S600 coupé by long-time single-seater champion Jim Palmer and early Bay Park promoter and race car owner, Feo Stanton. The little Honda was entered in the October 1965 Gold Leaf Three Hour Challenge endurance race at Pukekohe for exotic imported cars. The S600 ran well, and was competitive with the Mini Cooper brigade until brake problems caused a meeting with the bank at the Elbow. The car resumed, but at a reduced pace.

While these initial local race activities involved early Japanese performance machines, the next milestone certainly opened a few eyes. This came at the inaugural running of the B&H 500 race held at Pukekohe in October 1968.

Running a limited-edition performance car was one thing, but believing that an early locally-assembled Japanese production sedan could seriously hound the favoured Zephyr V6s and hot-rod six-cylinder Vauxhall Victors was liable to have you cited for suspect delusional tendencies. Before the race, that is!

In that B&H 500, a race for standard production cars, the potent little Datsun 1600 was driven expertly by front-line single-seater driver Dennis Marwood, along with Brian Innes. It embarrassed a number of the larger-capacity front runners as Marwood moved through the field to the business end, with the Datsun proving both fast and reliable, while many of the Zephyr and Victor brigade struck reliability issues under pressure. Eventually Dennis finished fourth outright, his well-driven Datsun having punched far above its weight. Another 1600 Datsun finished in seventh place. The next four-cylinder machine home, the previously dominant Fiat 1500, could only make 10th.

These were accurate indicators of a shift in power towards Eastern racing marques in various categories of local motor sport over the next 20 years. Lightweight, high-performing Japanese machinery endowed with seemingly bulletproof reliability would continue to hunt down bigger-capacity rivals over the following years, particularly in production car races. Mazda’s four-door rotary-powered Capella would also prove to be a giant killer and, a few years later, would almost humble its much bigger-capacity Chrysler Charger and Leyland P76 rivals.

By the mid to late ’70s, the panorama of New Zealand motor sport was changing. The previously dominant V8-powered saloons and single-seaters were on the wane, too expensive and unreliable to be sustainable.

The time was ripe, and Reg Cook on the asphalt with Datsuns, and Bill Shiells’ expertise with Mazda rotaries, was about to transform both the rally and dirt- oval saloon scene. Cook and Shiells were magicians as engine developers and tuners, coaxing massive amounts of power from relatively small Japanese engines.

The rest, as they say, is history. For many years from the mid ’70s to the early ’80s, Cook and his various Datsun coupés were almost unbeatable as he reigned supreme in New Zealand’s premier saloon-car racing championship, the Shellsport series. He won the outright NZ Saloon Championship, in the 1300cc category in 1975–’76, and again in 1977–’78, by which time his normally aspirated 1.3-litre Datsun engine was developing a whopping 122kW (163bhp). He repeated his success in the larger 2.0-litre class with two more title wins during the early ’80s.

Meanwhile, Ron Kendall’s Shiells-built 13B rotary-powered speedway Mazda Capella proved its giant-killing capabilities against more cumbersome and heavy Australian and US V8-powered rivals. Equally, Rod Millen was pretty much invincible in the NZ Rally Championship, winning the outright title three years running, from 1975 to 1977.

Later, of course, came the great Nissan Skyline Group A saloon era of the mid ’90s. Group A proved to be tailor-made for Japanese engineers as they developed highly refined, high-power force-fed engines that were then shoehorned into lightweight cars. As they became the dominant force in Group A racing, the old myth that there’s no substitute for cubic inches found itself on very shaky ground. Eventually the local Australian manufacturers, realising that their revered V8s would never get on terms with the crushingly successful ‘Godzilla’ Nissan Skyline, pulled the plug on the series. Instead they went back to the future with a new Falcon- and Holden-only V8 series in 1993. When you can’t beat ’em, what’s the best solution? Easy, legislate them out of the contest!

Japanese performance cars on New Zealand roads

The above potted competition history aside, it’s the sheer charisma of early Japanese machinery in its closest-to-original road form that truly gives me a buzz.

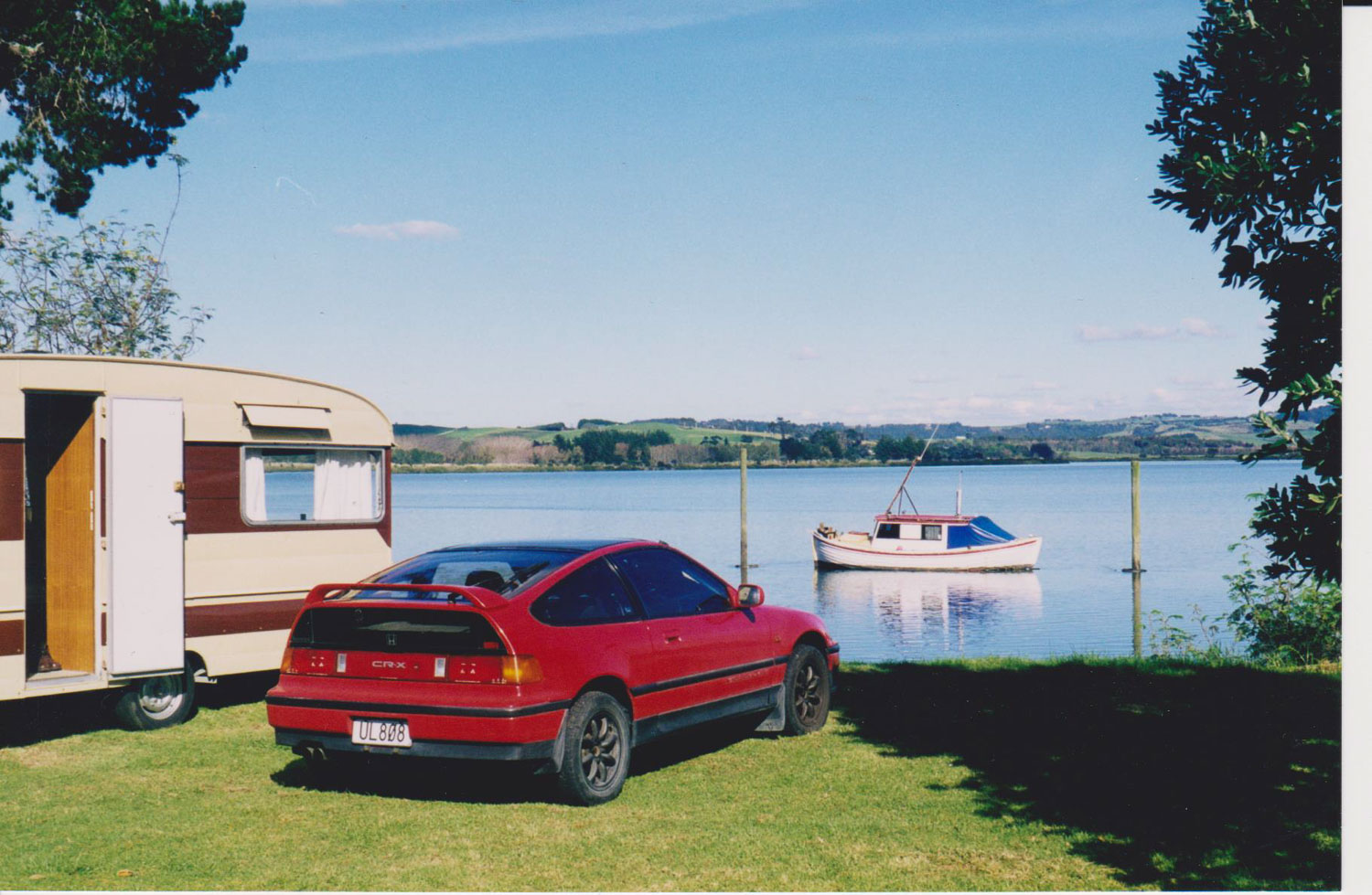

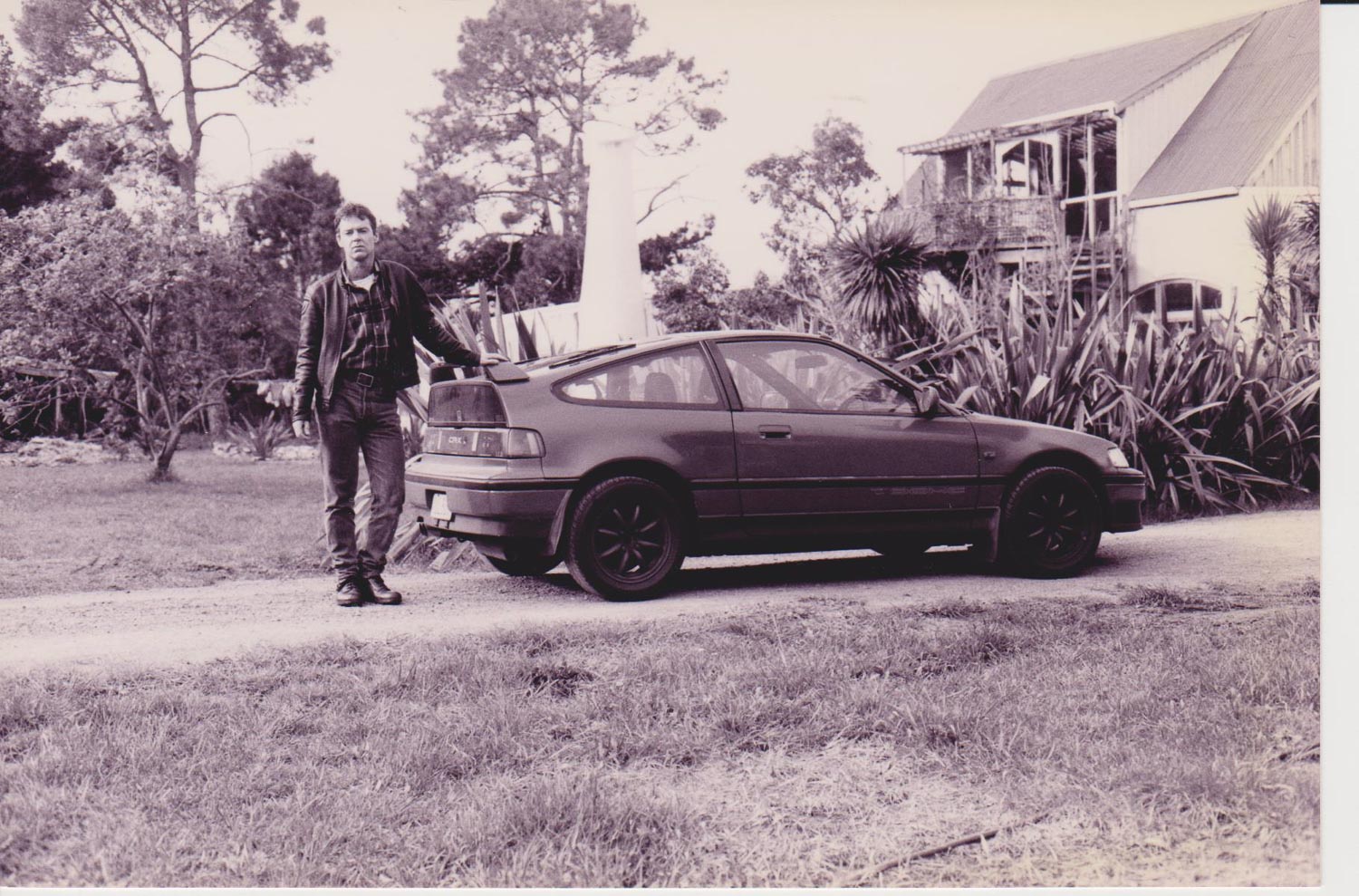

Many of my favourites stem from the first wave of the ’70s as well as those from the later, more technologically evolved ’80s. The early Toyota Corollas of the ’70s plus Datsun coupés, the Mazda Capella and the mid ’70s Mitsubishi Galant GTO were all sharp-looking runners. In the mid ’80s Nissan Skylines, Toyota Supras and Mitsubishi Starions all appeared in Group A racing, and I have a strong affinity for them as well, having owned a Group A–based FJ20-powered Nissan. I also owned a very quick 1987 twin-cam–powered five-speed Honda CRX Si complete with Watanabe alloy wheels wrapped with low-profile Bridgestone rubber. It went like a scorched rat, and stuck to the tarmac like a go-kart.

Bear with me — I even wrote a poem celebrating the Honda’s charms. I’ll only quote a few lines here (apologies to Brian Wilson):

She’s my lil’ red CRX,

We got a good thing goin’ here,

the suburban screamer and me.

Shades on, he’s combat hyped,

Saturday morning, in the tarmac war.

Lashed down low,

he’s clutching the leather wheel rim,

and pumping the metal plates.

She’s my lil’ red CRX,

five-speed, 16 valve, twin overhead cam rocketship.

Japanese high-tech wizardry,

blitzkrieg performance, for the inept masses.

My 1985 Nissan Silvia/Gazelle, with its FJ 20 turbo Group A–based high-performance mill, was the most exotic Japanese cult car that was ever in my possession. It boasted racing driver Matt Halliday as a previous owner listed on the papers — which I still have. By the time it came into my hands the Nissan had been seriously caned, and despite being in need of a rebuild, it was still a highly impressive piece of kit.

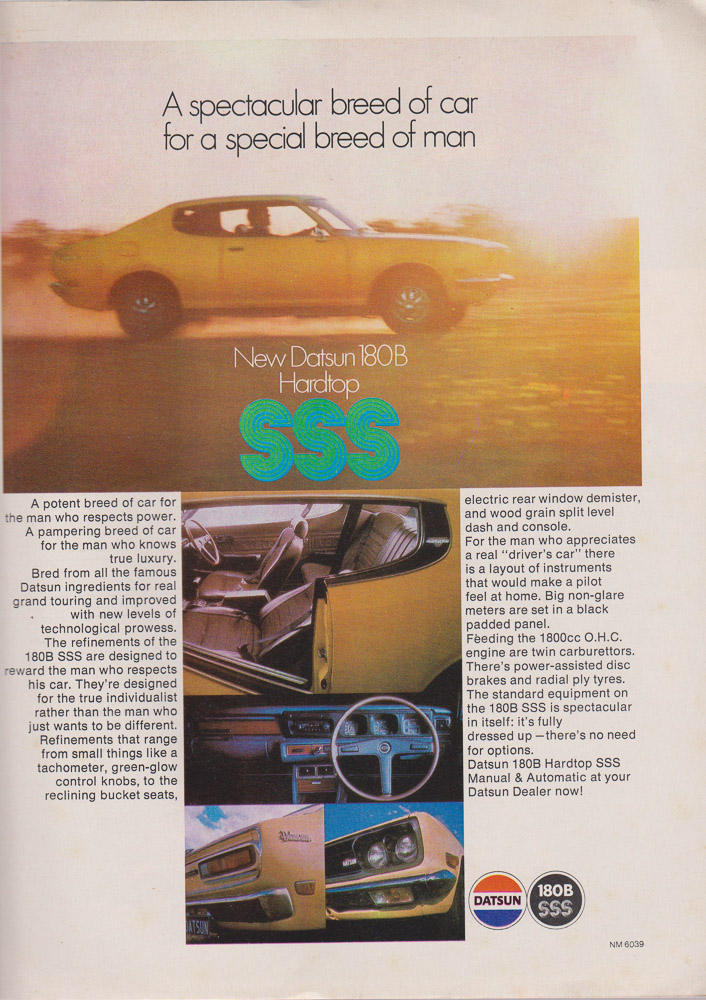

I’m always on the lookout for interesting early pieces of Japanese tin, original runners, derelicts or even production dirt-track machines. An ultimate fantasy of mine involved the unlikely possibility of me stumbling upon an original survivor with early B&H endurance racing heritage on its CV. Wouldn’t that be cool, to track down, for example, a mid ’70s Datsun 180B two-door or a late ’60s Datsun 1600, with matching numbers and genuine B&H credentials?

My greatest automotive regret was passing up on a genuine 1985 R30 Skyline coupé, Turbo 2000RS FJ20 (Group A production version) being offered at a car fair in the mid ’90s for around eight grand. It was the car I’d always wanted, but I managed to convince myself it was too much. What was I thinking of? The asking price was bugger all, and these babies are now very serious collector’s pieces, and priced to match.

Toyotas have been my other main passion. I’ve always wanted an early ’70s Corolla coupé, like the modified version that Dick Sellens raced in the up to 1300cc NZ Saloon Car Championship in 1971–’72. In 2001 I knew an old lady on Auckland’s North Shore who had one in nice condition, and for several years she convinced me that I would be the lucky guy to be first in line when she was ready to part with the car. I would ring her regularly to let her know I was still keen, but somehow she never reached the crucial decision. Instead, I acquired a 1983 Toyota Sprinter, and that was a revelation. It had the earlier, glorious-sounding eight-valve twin-cam motor — possibly the rare and now revered 2T-G engine — that just wanted to rev, winding out in an exhilarating blast of acceleration. I loved driving the Sprinter, even though the bodywork wasn’t so flash, and it opened my eyes to what a magnificent engine the Toyota twin-cam was and still is.

I also find early examples of the ordinary four-door saloons, like late ’60s Corollas and Datsuns, appealing. These cars were amongst the first locally assembled Japanese vehicles in New Zealand. In particular, Toyota has a long history in Thames, just south of Auckland. Campbell Industries based itself there, and was probably the first to assemble Japanese cars with the Corolla KE10 in 1968.

The small four-door-style sedans built during this early period of local assembly have almost all disappeared, as they were unlikely candidates for restoration. The very occasional ones that have survived have often been saved by young petrolheads looking for something a bit different.

Those cars represented the best value for money back then, and now. Like the 1969–’70 1166cc Toyota Corolla four-door, equipped with front disc brakes, carpets, a full ventilation system, two-speed wipers and radio all as standard equipment. It may seem absurdly basic now, but almost none of Toyota’s contemporary rivals offered a comparable package of features as standard, in the same or even higher price brackets. Holdens were notoriously archaic when it came to standard fitments during this period.

The humble Corolla, of course, later became the flag bearer for the success of the Japanese car industry. While initial sales of the Toyota were sluggish due to public prejudice and media-promoted myths of poor quality, once the evidence was clear that they were well-built vehicles, the public embraced them. Its huge popularity and matching sales figures enabled Toyota to grow and develop a highly enviable reputation for fine engineering and quality. It also provided financial backing for the further evolution of later, more sophisticated models.

Japanese Imports: performance for the masses

It was the decision to change import tariffs and loosen up the regulations in the late ’80s that allowed a massive influx of Japanese imports into the country. Very much a two-edged sword, this move hastened the decline of local car assembly while allowing those who couldn’t afford a European performance car the opportunity to get behind the wheel of some serious performance machinery.

With almost trance-like disbelief, I was intoxicated by the dazzlingly rakish Eastern imports — almost all of them within my price bracket. After many years of driving tired and worn-out British and Australian cast-offs, I suddenly found myself in charge of a sexy two-door machine with mind-blowing features and capable of neck-snapping high performance. Cocoon-like wraparound dashboards, deeply sunken dials and sporting steering wheels — as far as I was concerned, we’d all been been delivered a miracle, and were ready to rock.

In 1990 a good friend and I lashed out our hard-earned readies and bought a couple of sleek two-door coupés. My friend purchased a bright-red 1981 E70 Toyota Corolla Sprinter, while I went for a 1982 R30 Nissan Skyline Turbo. I can still remember the surrealism of it all — our previous rides had been 10- to 15-year-old old bangers that were, in reality, well past their use-by dates. By comparison, this was a stratospheric change into some science-fictional wonderland. Apart from a locally-assembled no frills 1982 Datsun Sunny I had bought in 1983 for an arm and a leg, the Skyline was my first experience of a fully-optioned Japanese performance car. It was as if someone out of nowhere had shoved me behind the wheel of the space shuttle, the Nissan was so futuristic.

Subsequently the ’90s and the early years of the new millennium saw me indulge myself with five different coupés — the four Japanese missiles already mentioned, and a classic ’70 Holden Torana GT-R XU1.

While the Torana was fast, it was raw and uncouth, and its road manners were way inferior to the best Japanese performance cars I owned. They all had character, but as a balanced driving machine the Japanese beasts from the East were always more rewarding to pilot.

It’s been a few years since I’ve had a piece of iconic Japanese performance in my shed, but I don’t discount the possibility of owning another if the right piece of Rising Sun iron presents itself at the right price. As mentioned earlier, an original machine with genuine B&H history would be of interest — and it wouldn’t need to be anything exotic, like a Mazda RX-2, and could even be a humble Corolla.

What I have endeavoured to record on film (much of it on display over these pages) are some images of the cars from a now rapidly disappearing time when they were still used as daily runners. The photos will hopefully bring back some memories for enthusiasts, and maybe inspire the rescue and resurrection of a few more of these great automobiles.

This article was originally published in New Zealand Classic Car Issue No. 296. You can pick up a print copy or a digital copy of the magazine below: