“Donn has stayed in rotary mode since last month’s column on Mazda’s RX-7, and now recalls driving the NSU Ro80 on loose-surface roads, pointing out that while Mazda made the Wankel engine work, NSU’s award-winning saloon was doomed to failure because of that same revolutionary engine”

Every now and then a car comes along as a rising star, yet a star that sometimes fades. Recently I was discussing cars with a chap who drives a modest Japanese sedan now he’s in his senior years, but in his younger motoring days he owned several specialist vehicles — and one stood out above all others.

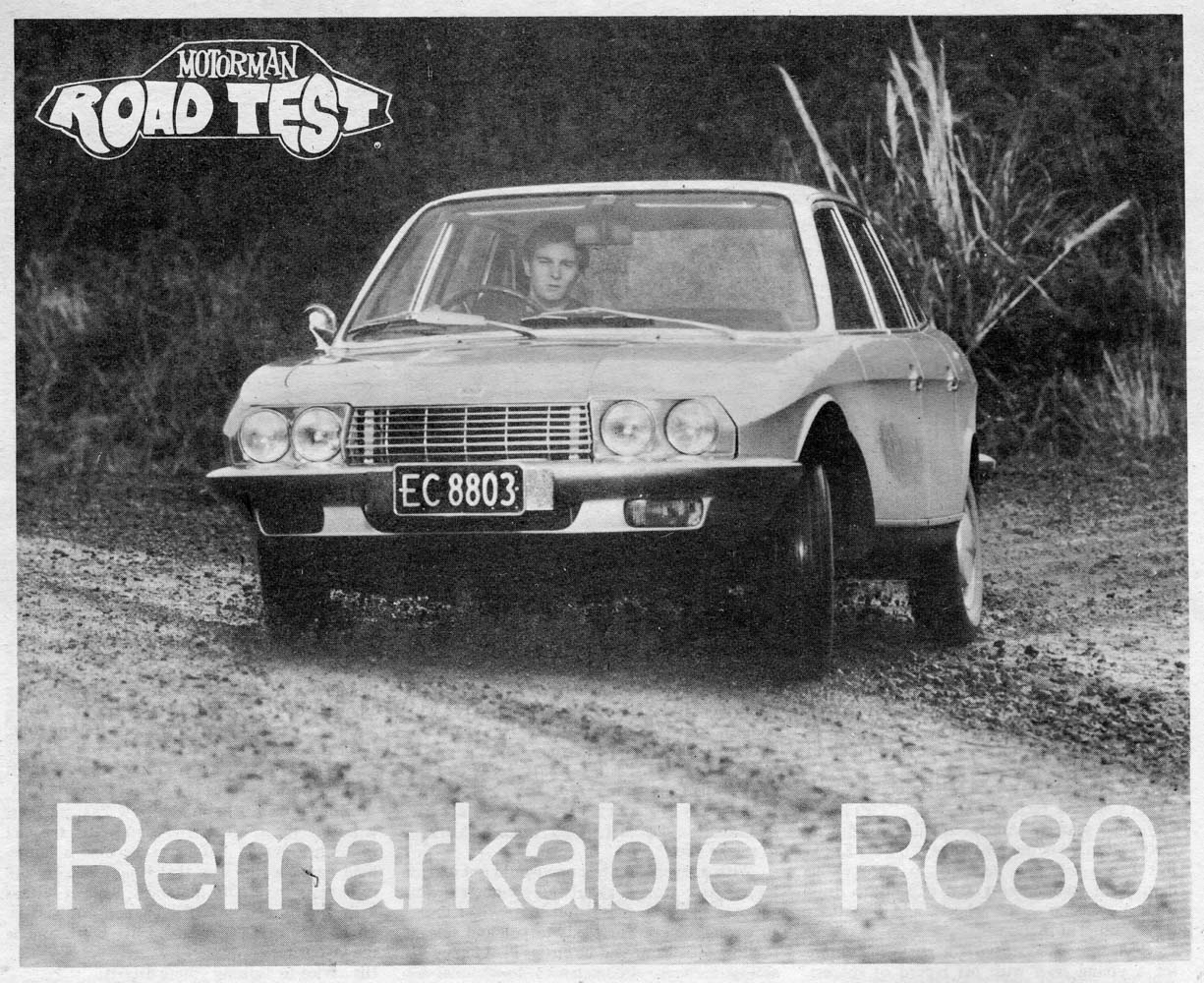

He was initially impressed with the NSU Ro80 during his test drive, when the dealer put two inside wheels into the loose gravel at relatively high speed, before slamming on the brakes. The car remained totally stable, and at no time looked like losing control. It was a convincing demonstration that clinched the ownership deal.

The dealer in question was Jonathan Gooderham, sales manager for local NSU distributor, P Coutts and Company, of Auckland. He recalls the braking test on the western motorway heading for Henderson, and how the outcome was a certain selling tool — however, the car’s electronic gear shift and brake pedal caused some alarming problems. Prospective buyers were encouraged to anchor their left foot against the bulkhead when changing gears, to prevent sudden unwanted braking.

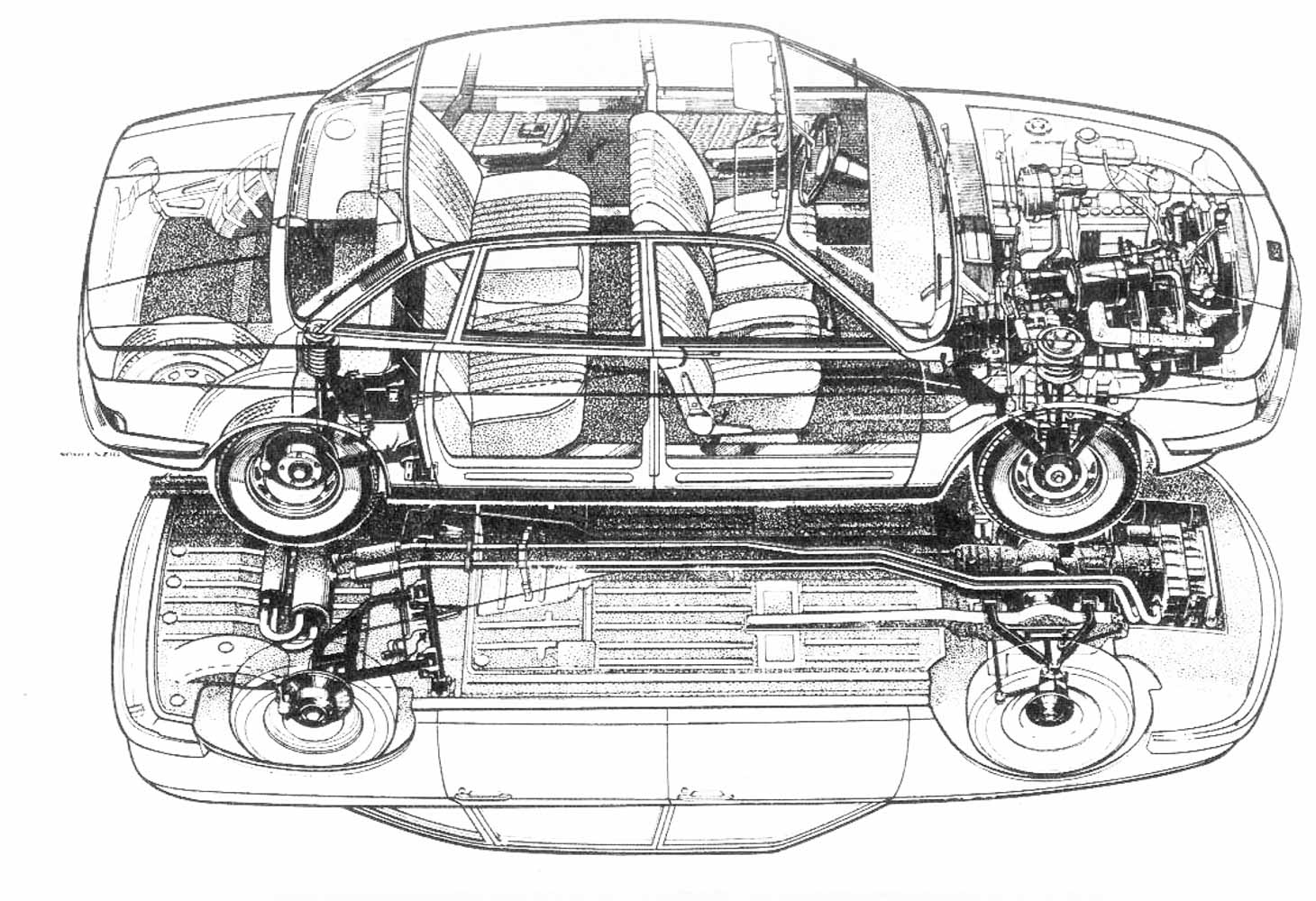

There were at least two major rear-end rebuilds in Auckland initiated by drivers accidentally slamming on the Ro80’s stunning inboard-mounted four-wheel ATE-Dunlop disc brakes.

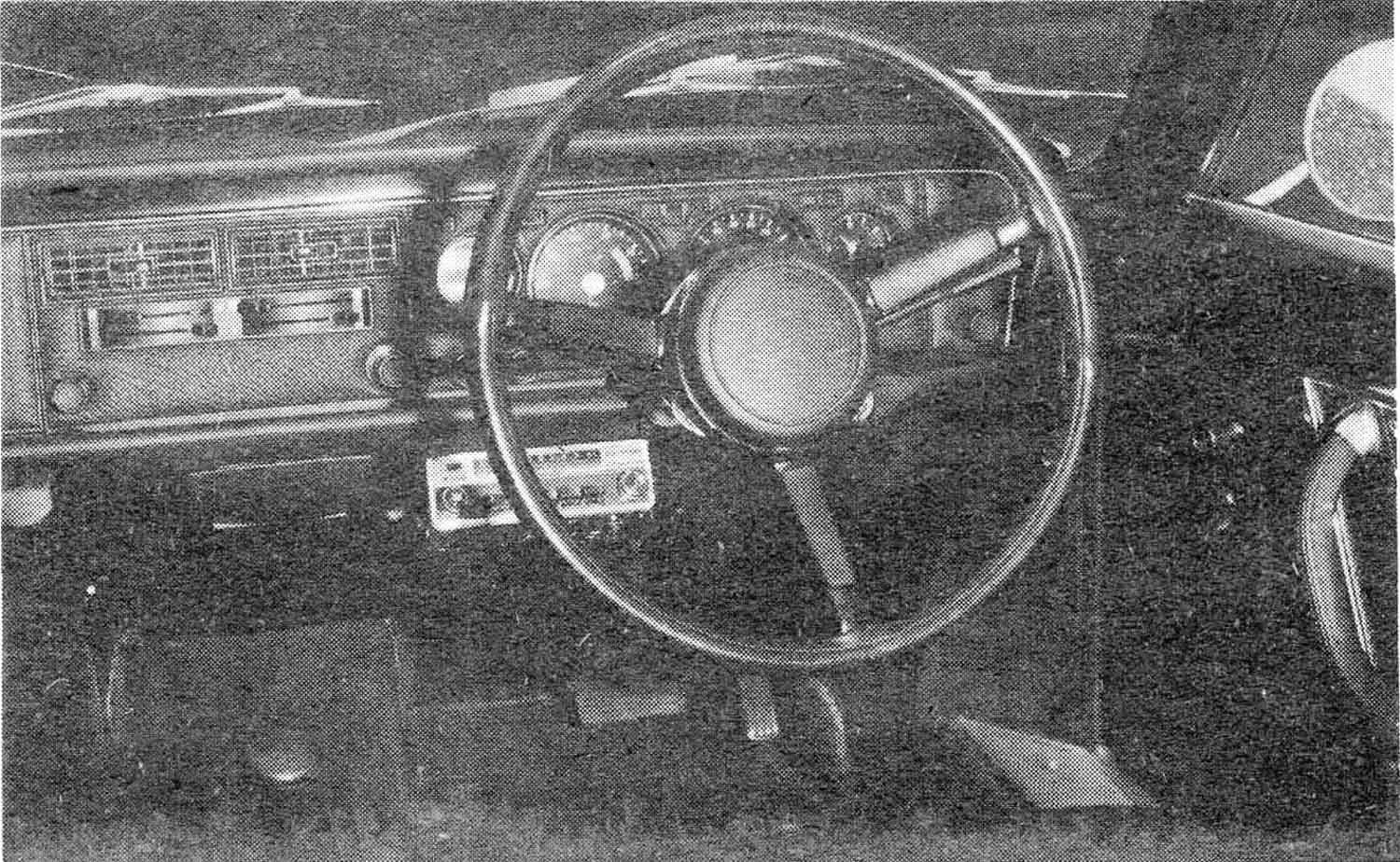

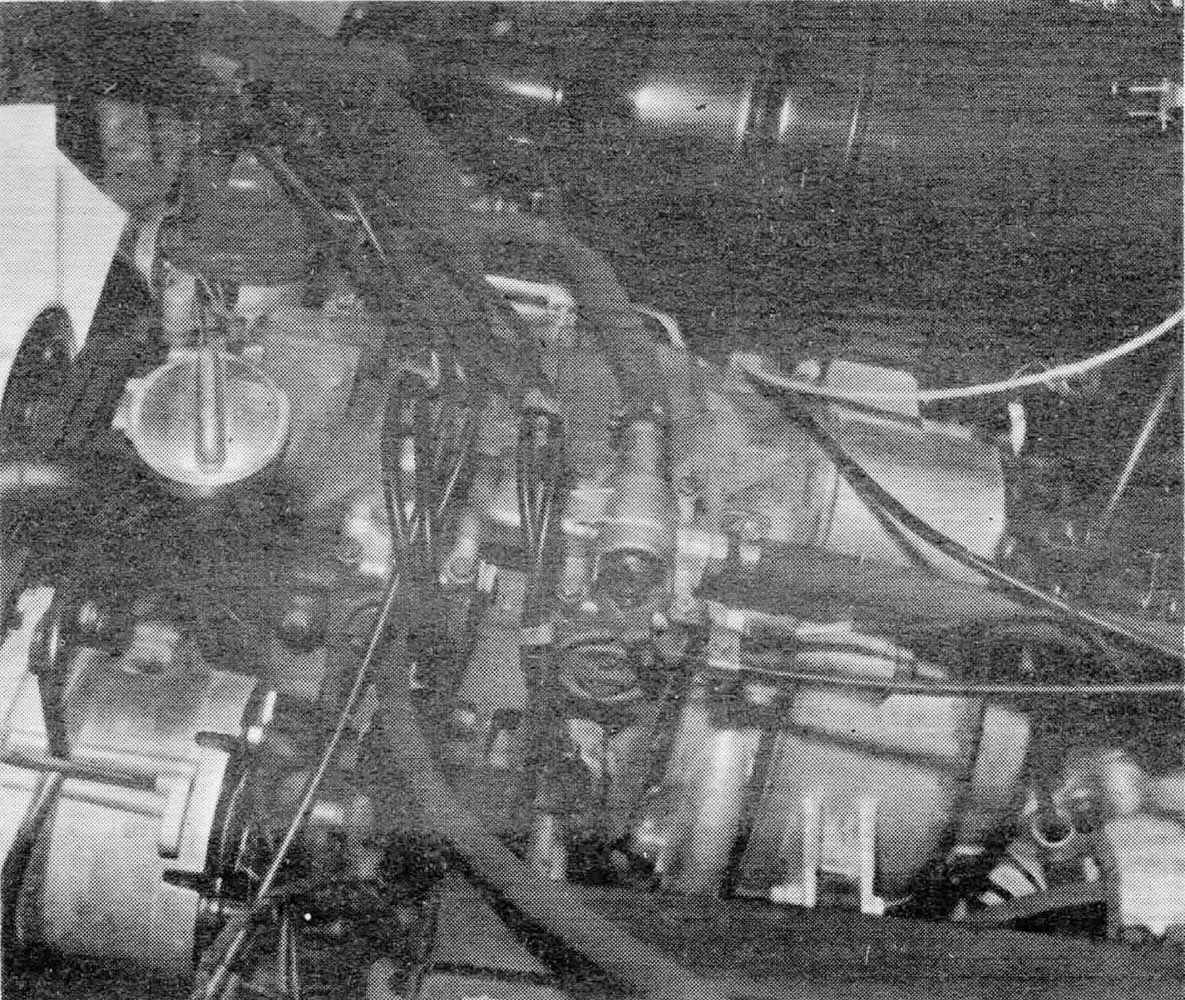

The rotary engine was linked to a three-speed Fichtel & Sachs all-synchromesh electrically operated clutch used in conjunction with a torque converter to give two-pedal control with full manual override. Changing gears simply meant easing the accelerator and moving the floor-mounted lever, making the car almost as lazy to drive as a full automatic.

The clutch disengages when activated by a touch-sensitive micro-switch on the gear lever, and because of the high-revving ability of the rotary, three speeds are more than adequate for the job. However, just brushing your knee against the gear lever can disengage the electro-pneumatic clutch — that’s a bit unsettling if you happen to be on full throttle.

On test

Those local braking demonstrations reminded me of my Ro80 road test on Auckland roads 46 years ago — which opened with the comment: “Any car in which you can take both hands off the steering wheel at 100 miles an hour with nary a whisker of drama is truly outstanding.”

This was a family car for the ’70s already available in the ’60s, and a vehicle that attracted the attention and wallets of several prominent Auckland business people who were more used to driving Jaguar XJ6s, but were fascinated by the technical brilliance of the upmarket German saloon.

“It was a truly amazing car with that long-travel suspension, great ride and fantastic roadholding as long as you were willing to let it really lean into a corner. I have happy memories of those cars,” says Jonathan, in spite of numerous motor problems that made NSU’s financial situation even more precarious than it already was. Gooderham remembers rotor-tip wear and lots of engine rebuilds by Steve Oxton, father of former champion racing driver David, tempered by the fact that the rotary engine was easy to strip down.

Of course, it was not the road manners that marked out the NSU as something rather special but the Wankel twin-rotary engine, the power unit which ultimately spelled disaster for the model. There seemed few signs of unreliability in my 1969 road test when NSU reported that the engine’s oil sealing was now perfect. Oil consumption was confined to a planned spray through the twin-choke Solex carburettor to help internal cooling and lubrication. Never before had I driven a car which sounded so smooth and happy at 6000rpm.

We ran the Ro80 to 130kph in second gear (6250rpm) and it still felt unstressed, and at a lazy 115kph (under under 3800 revs in top), all the windows could be lowered with an absence of cabin draught. My notes read, “The magic 100 miles an hour — 160kph — represents 5300rpm, and even at this speed the NSU is just starting to use its long legs. A remarkable motor car.”

A rare classic

Despite being almost half a century old, the Ro80 — Ro for rotary and 80 for the NSU drawing-board design number — is a rare classic car with an ability to meet modern-day machinery head-on. Little wonder with its wind-cheating shape, advanced specification and unique power plant it was years ahead of its time. Take away the rotary and the Ro80 would still have been a revolutionary car.

During the honeymoon months of its launch in 1967, the Ro80 won the 1968 European Car of the Year award, and was hailed by many as the car of the decade. It represented a huge upward step for NSU, costing more than twice as much as the marque’s other models. Indeed, you could buy four NSU Prinz 4 saloons for the same price as one Ro80.

Yet the audacious rotary engine that was so much admired would herald the car’s heroic failure. Although in production until 1977, in the Ro80’s last three years annual sales barely amounted to 2000 units, and total production for the decade was just 37,400. Second-hand Ro80s were almost worthless in the ’70s, prompting some frustrated owners to repower the car with Ford’s V4 Essex reciprocating-piston engine simply because it fitted into the NSU. Only a handful found owners in New Zealand, where the first examples cost $6000. By 1972 the retail had risen to $8950, and when the last new Ro80s arrived here in 1974 the sticker price was $10,900. The total number of new examples to hit our shores was barely more than 30.

NSU had first fitted the rotary to the small Spyder in 1964, building 2375 of these over a three-year period, but as the world’s first front-driven Wankel-engined luxury saloon, the Ro80 was a much bigger deal. The smooth and light Wankel motor was on the move, with NSU working with Citroën on a small rotary-engined saloon, and Mercedes-Benz making advances with its appealing triple-rotor experimental power plant, even coming close to offering a four-rotor engine in the W123 sedan as an optional unit before cancelling the project at the 11th hour.

Citroën launched the Birotor version of the popular GS in October 1973 — unfortunately, the same month the Middle Eastern oil crisis broke, and the car was a dismal failure. Only 847 Birotors were sold, and they were so troublesome Citroën bought back most cars and crushed them!

Meanwhile, NSU slung its 85kW (115bhp) Wankel into the nose of the Ro80, only to be faced with reliability and fuel-consumption concerns that were never truly resolved. The future all seemed so much brighter during my test of the car in mid-1969, when I reckoned “the rotary engine is here to stay.”

Weighing up the all-independent suspension, four-wheel disc brakes, three-speed semi-automatic transmission, superb steering and handling and high comfort levels, not to mention the Wankel, and the Ro80 made most other luxury cars of the day look distinctly dull.

Damaged goods

The failure of the rotary in those early days was foretold. Herbert Brockhaus, head of testing at NSU, warned the company board of problems months before the Ro80’s launch. He said there had been insufficient testing of seal inserts, trochoid rotors, and the eccentric shaft and bearings, believing NSU needed two full years to perfect the engine. But engineers and the board were convinced they could solve the problems more quickly.

Unfortunately for them, and for the brand, Brockhaus was right, and it took precisely two years to fix premature rotor-seal wear. By then the damage had been done to the marque’s reputation, and NSU merged with Auto Union in 1969 — both swallowed up by Volkswagen. VW-Audi persevered with the Ro80 until 1977, but by then the car was only available to special order, and was attracting few buyers.

Things could have been so different. Styled by Claus Luthe, who later became head of design at BMW, the attention-getting Ro80 was clearly ahead of its time. NSU spent almost four years testing the car’s shape in a Stuttgart wind tunnel, and the resultant dart-like profile with a low frontal area rising to a high tail translated into a 0.355 drag coefficient — some 35 per cent lower than the average saloon of the day. Indeed, Audis into the ’80s and ’90s would inherit much of the styling poise of this NSU.

Today, the Ro80 still feels light, modern and airy, with a generous interior and a certain amount of ambience. Gooderham remembers the car’s slippery drag coefficient as a major selling point.

The driving experience

Moderate use of choke is needed from cold, and the engine soon settles down to a rather noisy two-stroke-sounding idle. On the road the 200kph Ro80 seems to become quieter the faster it goes. Even if the rotary could benefit from more low-end torque, the turbine-like smoothness is always a treat, and the car’s refinement means it is quicker than it feels.

With MacPherson strut front suspension and a semi-trailing-arm independent rear with coil springs, both ends were engineered to give an opulent ride as well as superb handling and roadholding. On the road you would soon fall in love with this front-wheel-drive sedan with a ZF power-steering system that gave the sort of feeling and sensitivity virtually unknown in the ’60s.

The car was fitted with 14-inch-diameter Michelin XAS rubber, the first tyre with an asymmetrical tread pattern, and then the later XVS flat-tread tyre with rain-drainage channels. Weight distribution is 60/40 biased, of course, to the front, but the car has the sort of poise and control that was rare 40 years ago.

At launch it was difficult to think of a road car which could equal the handling and roadholding of the Ro80. This was a vehicle that came closer to dynamic perfection than any production saloon before. On wet and twisty roads its behaviour was impeccable, and well suited to New Zealand conditions since the car was especially good on loose metal or gravel surfaces.

Faced with crippling warranty claims, NSU fitted later Ro80s with tougher seals and chamber walls plus transistorized ignition, but these upgrades were only a partial fix. In easy town and urban running too much petrol washed oil off the chamber walls and, while the rotary objected to extended low-speed running, owners had also to be watchful of high-revving abuse of a power unit that seemed ever so willing. To avoid excessive tip-seal wear resulting from high revs, the last of the production cars came with a warning buzzer to prevent over-revving.

The secret, said some, was to warm up sensibly and then drive quickly, since the plugs were inclined to foul in traffic. However, NSU was never able to obtain the sort of reliability that Mazda achieved so soon with its RX range of cars. As Ro80 production neared completion, critics cried the rotary engine would never succeed because of three factors — tip-seal unreliability, high emissions and heavy fuel consumption.

Dr Felix Wankel, who died in 1988 aged 86, never gave up on his engine, and continued development right until his death. Yet perhaps the inefficient combustion chambers would never be able to match the fast improvements that the demands of a worldwide oil crisis forced upon more conventional reciprocating-piston engines.

Learned motoring critic Leonard Setright reckoned more investment and development could have overcome all the above-mentioned deficiencies, and said the Wankel engine was like a newborn babe having to contend with an established engine type that had already spent 70 years maturing. The late Setright argued the rotary was an elegant solution that car-makers had overlooked, blaming them and politicians alike for the failure of the unique power unit.

Nevertheless, this oddball hard-to-start, smoky, thirsty car is a genuine classic, but a rare vehicle to find, and one that is likely to have a troublesome power plant. The Ro80 may sound like an elderly hair dryer, but will wow you with its dynamics and individuality. Remarkably, this is a car that has not dated, merely matured — and for that it should be remembered with respect.